The term “natural gas” was always an odd one to me. I mean, yes, gaseous methane (natural gas is 70-90% methane) we pull from inside the Earth is a naturally occurring thing, so all of the elements are there: “gas” + “natural.” But this kind of naming structure isn’t used for most other “natural” things. If it were, then where is the “natural potato” to be found? There are plenty of natural things that we don’t call “natural” because there isn’t really an alternative to warrant drawing a distinction. There is no competing “artificial potato,” so there is no need for us to classify a “natural potato.” Every “potato” is understood to be a “[natural] potato.” But there’s no commonly known “artificial gas,” so why do we have the term “natural gas?” There might be some argument to be made in that it draws a distinction between itself and “gas(oline),” but the real answer is that there really was an “artificial gas;” though, it was called “manufactured gas” and it fell out of widespread use by the 1950s.

Whereas natural gas is produced from some form of well pulling it out of the ground (often through hydraulic fracturing, “fracking”), manufactured gas was produced through intentional combustion of a variety of materials like coal and coke (a coal product made from heating coal in a low-oxygen environment). Manufactured gas began to be used in the early to mid 1800s as a main energy source for purposes like lighting and cooking. It eventually became displaced by primarily-methane natural gas due to pipelines facilitating volumes of natural gas that manufactured gas plants couldn’t compete with and due to natural gas’ higher Btu (British thermal unit, a measure of a material’s heat content); natural gas is able to heat more when compared with the same amount of manufactured gas. So, the distinction between one gas existing in the ground being “natural” and the other having to be created through an industrial process being “manufactured” makes sense and gives us the reason why we have “natural gas” today without a single “natural potato.”

While history teaches why we have the terms we do, today, “natural” is not likely to evoke ideas of the heavily industrialized process of fracking that currently produces most natural gas. We know that “natural” can be used in multiple ways: “natural talent,” “natural law,” and “natural ingredients” all spring to mind. “Natural” is often associated with what is good, authentic, and healthy. It is juxtaposed morally with the oft-maligned “artificial.” Just look at the heavy focus of food labels which emphasize their product being made with, as we have seen, “natural ingredients” or “only natural flavors” (and in the negative: “never from concentrate” or “never artificial”).

The term “natural gas” can have a similar effect by making people think of the primarily-methane substance (and the process for acquiring it) as cleaner and healthier than it actually is. A recent study published by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication shows that this is the case.

The study looked at people’s opinions and associations of words and terms like “natural gas,” “methane,” and “methane gas.” It found that while “natural gas” was associated with “themes like energy, clean, fuel, and cooking,” “methane” terms were associated with “themes like gas, cows, greenhouse, global warming, and climate change.”

It also found that the overall feeling towards the terms were different. Partitioning those surveyed by political party, the study found that both Democrats and Republicans had favorable views of the term “natural gas,” but both had unfavorable views of the terms “methane” and “methane gas” (there was an even split on “natural methane gas” between the parties). While Democrats’ views on all of the terms were more negative than Republicans’, the nonetheless shared feelings of positivity about “natural gas” and negativity about “methane” are striking.

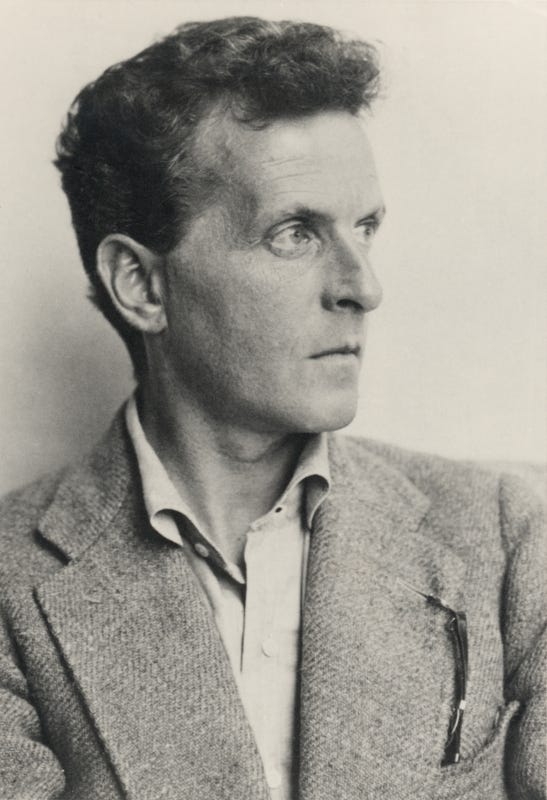

In light of these differences, it seems clear to me that continued use of the term “natural gas” would simply be linguistically and, therefore, materially irresponsible. To support such a claim, I must, finally, incorporate the third prong of my titular trident, Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951): a hugely influential Austrian-British philosopher who dealt largely with philosophy of language. Not getting caught up in the admittedly intriguing details of the conflicting road to his final linguistic conclusions, in his last and posthumously published philosophical work, Philosophische Untersuchungen or Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein set forth a particular conception of language and meaning relevant to our discussion here.

Contained in the work’s 43rd remark is the following (bolded emphasis mine):

For a large class of cases of the employment of the word “meaning” — though not for all — this word can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.

In contrast to past philosophical notions of language and meaning that sought to arrive at a word’s meaning through structured analysis and philosophizing, Wittgenstein proposes that a word’s meaning is found straightforwardly through how speakers of the language use the word. This forms part of a broader theory which views language as an extremely socially informed, and in some ways socially dependent, phenomenon.

The reason I bring up Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language in this piece about natural gas and methane is that I think it can serve as an informative backdrop and framing to help explain why “methane” (or some similar word or phrase) should replace “natural gas” in our speaking and writing. In light of the meaning-as-use paradigm, native speakers using the term “natural gas” when referring to the primarily-methane substance usually pulled from the ground via fracking are not straightforwardly wrong in their word choice. When we say “natural gas,” the meaning the of the term is understood from our use of the term. But, I argue, our use of the term, when understood to carry the associations found by the Yale Program’s study, is slightly out of line with the reality of things. When we say “natural gas” and connotate — which we do in the aggregate — positive ideas of clean energy, we are misleading ourselves and our listeners into thinking that the primarily-methane substance usually pulled from the ground via fracking is among the group of those energy sources that does not put us in danger and does not exacerbate climate change.

While the primarily-methane substance usually pulled from the ground via fracking does cause less emissions than, say, coal (and by a decent margin), such a bar is not particularly noteworthy in height. It is a better alternative to some of the dirtiest energy sources, but it is not an energy source that can be here for the truly long term if we are to fully combat climate change; it should not be treated as such. CarbonBrief gives a good account of the IPCC’s caveat-filled perspective on the matter:

[The IPCC] indicates that natural gas could play a role in the decarbonisation effort – but only in a controlled way, as a substitute for higher-emitting coal, and with emissions from the energy sector as a whole shrinking rapidly throughout this century.

Because the term “methane” brings with it social connections and connotations to things like climate change and greenhouse gases, it is a less misleading term to use to describe the primarily-methane substance usually pulled from the ground via fracking. When we use the term “methane,” we mean something slightly different than when we use the term “natural gas.” Even though it may seem like we (can) use the terms interchangeably, and even though, if asked, we may say we use them interchangeably, the subtle differences found in what each term evokes in listeners illustrates that they can and do have different use cases and, as such, different meanings. Thus, in choosing which term to use, we should recognize which use-case is our more preferred and use the appropriate, corresponding term. If we agree that the better use-case is the one which highlights the real connection with greenhouse gases and climate change (which I think most people reading this newsletter would be wont to do) rather than downplays it, then our choice is clear: it must be “methane.”

In our efforts to fully recognize both the threat that climate change presents and the pervasiveness of that threat’s causes in almost every aspect of our lives, I believe we should actively alter our common parlance to use “methane” or “methane gas” (or another like term) when we would have previously used “natural gas.” Methane currently accounts for somewhere close to 23% of the world’s energy generation. It is not something that will or can go away overnight. All of those people supported by it must be able to acquire energy from another source. But those other sources are out there. The change very much can be done. We just need the political will and social pressure to do so. Hopefully, choosing our words with care to accurately reflect the state of things can help move along the social realizations and calls to action that we need.